A pony is a pony

even when it loses its license

I watched cowboy Hunter ride over the hilltop the other day. He’s our freshest cowboy, he just came over from Golden Diamonds Ranch. They are a posh place. They’re by far the most pretentious ranch around here and in some ways, they are more of a resort than a ranch. They only hire “the best,” so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Jack asked Hunter when he returned: “Why did you come here from Golden Diamonds?” The answer was not anywhere near what Jack had expected: “I lost my ICA license.” “What is that,” Jack wanted to know? Hunter replied: “Well, Golden Diamonds will only hire accredited cowboys, you know. It wasn’t difficult to get a license from the International Cowboying Association, though. Just do a handful of roping tricks. You’d pass in a glimpse of an eye.” Jack looked more and more bewildered, but he wanted to know more. “So how have you lost your license then?” The answer to this question would have come as a surprise to us a year ago, but no longer so. Hunter replied: “I posted online that I have never seen a cow that pretends to be a bull.”

Luckily, we are a ranch that appreciates honesty and we gladly pay for Hunter’s work regardless if he is accredited or not. We can actually see that he is a good cowboy. We don’t need any paperwork to attest to that. However, we’re becoming an exception to the rule. Large swaths of industries in the West meanwhile require some sort of accreditation from a professional licensing organization for their workforce. Maybe, the most well-known examples of professional accreditation are medicine and legal representation. In fact, most jurisdictions in the Anglosphere legally require Bar membership to practice the law. In medicine, the picture is even more complex. Most states or provinces will have medical boards who accredit medical professionals. Apart from state medical boards, though, there are a host of specialized medical organizations who will issue their own accreditation, such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) or the American Pediatrics Association. In spite of their names’ formal cachet, these organizations are not government institutions, but private professional associations, who are perfectly allowed to take funding from the industries they serve. Yet physicians will depend on these organizations to make a living in the corresponding field of medicine, since insurance companies often require certification from specialized boards to cover treatments.

The origins of professional accreditation can easily be understood. In times of more limited connectivity, it was not difficult to pose as a lawyer or physician. In those days, professional accreditation was a convenient way to ascertain qualifications. Bar associations would issue membership lists and in case of doubt, the central authority was only one letter, or in later days, one call away.

Professional accreditation organizations have always been aware that their members’ livelihoods depends on them. Therefore, they have historically set the bar very high to recall a member’s accreditation. Bar associations would only disbar members in case of flagrant misconduct, such as an attorney being convicted in a criminal case. Medical boards would only retract licenses in cases of blatant malpractice.

(Trust me, in case you subscribe, I will not retract your subscription)

The times seem to have changed, though. Recently, professional licensing boards have started to sanction members who express opinions not in line with the respective association’s leadership. An initial wave of such cases focused on professional opinions, but we are increasingly observing accreditations being retracted for political opinions too.

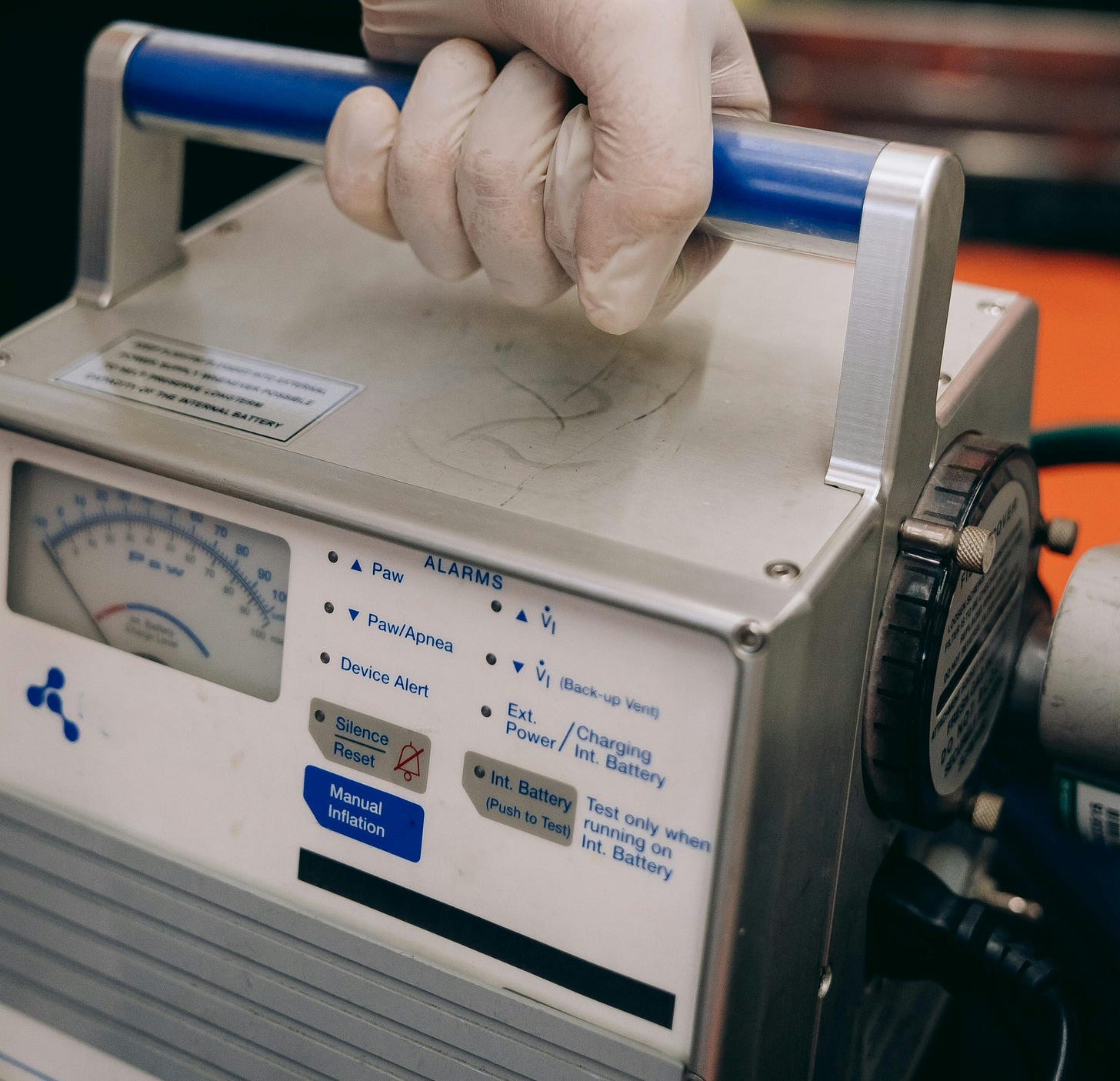

It is unclear when exactly this worrisome movement started, but even if it did not start during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was definitely accelerated by it. The early days of the pandemic ended up upsetting the lives of some of our best-accredited physicians. Particularly, a few leading urgent care physicians soon questioned official treatment protocols for COVID-19. In fact, it is an urgent care physician’s daily job to treat patients with a wide variety of conditions. Urgent care is urgent, so patients need to be treated within a limited amount of time and therefore, it is not uncommon at all for urgent care physicians to treat patients in good faith up to their best academic knowledge with a protocol that may be experimental. If off-label medicine ends up saving a patient’s life in urgent care, after all, why would we care if the protocol had been prescribed before? That all changed during the COVID pandemic. The official stance from the National Institutes of Health, Health Canada and other national public health institutions was that there was no treatment for COVID-19, so patients did not need to be treated until the situation got critical. In case they ended up struggling to breathe, patients were hospitalized and were put on a ventilator.

Some emergency room physicians with excellent track records immediately objected to this order of proceeding. In fact, they had treated many patients before with novel conditions, many of which successfully. While these doctors would acknowledge that we did not have a proven treatment for COVID-19, they were unwilling to just throw in the towel and not treat patients until they couldn’t breathe. They identified antivirals that had been successful against SARS-1, or MERS, such as chloroquine and its hydroxylated variant. These products were effective against closely related viruses and had been administered to millions of patients before, so there was a very limited risk associated with administering them. Recall that chloroquine is an anti-malaria drug in widespread use in the Southern Hemisphere.

The disadvantages of ventilation had been widely known before the pandemic. Very infirm patients may actually lose the muscle strength they need to breathe when assisted by a ventilator. Moreover, ventilator-assisted pneumonia is a well-documented condition. In simple terms, it implies that patients contract pneumonia due to the ventilation effect, which they would not otherwise. Given that there was a potential route to recovery and that ventilation was known to have adverse effects, I can only conclude that the emergency room physicians who decided to deviate from the official protocols, acted in good faith and did what they were morally required to do. That is, at least to try and treat patients to convalescence. Yet some of the physicians who took that route saw their licenses retracted for not following official protocols, for speaking up about that, or both. Even more shockingly so, that did not only happen at the height of the confusion caused by the pandemic. In fact, Dr. Pierre Kory and Dr. Paul Marik, two American urgent care specialists with excellent track records, saw their licenses retracted earlier this year by the ABIM, formally for “spreading misinformation.” So it is “unprofessional conduct” to try and treat patients for a virus that shares over 95% of its genome with a known relative (SARS-1) based on established treatments for that known relative, but it is the “standard of care” to induce ventilator-assisted pneumonia. This and related cases of license retraction have illustrated that licensing boards have morphed from being organizations who work in the interest of the broad public to organizations who will do anything to safeguard their stakeholders’ interests.

Based on the above information only, we might be enticed to think that the pandemic created an exceptional set of conditions that generated extraordinary behaviours. However, many examples of such authoritarian actions by professional licensing boards exist that bear no relation to COVID-19. When, back in 2017, Canada enacted new legislation that updated the Human Rights Act to include clauses for gender expression and gender identity (Bill C-16), Canadian psychologist and University of Toronto professor Jordan Peterson decided not to remain silent. He foresaw the newborn legitimacy for “gender identity” to generate a wave of perceived “transgender” cases, in which particularly young girls would be deluded into selecting the transsexual path as a solution to mental health problems. Since, several jurisdictions have gone farther than the Canadian Human Rights Act and have banned schools from notifying parents about the gender identity of their pupils, including California. However, in real life, the evidence is overwhelming that most of these “cases” concern mentally troubled teenagers who could end up perfectly happy gay adults if they chose to do so, which is why countries like the Scandinavian nations and the United Kingdom have started to dial back their support for juvenile gender transitions. Yet the “standard of care” according to organizations like the College of Psychologists of Ontario, or the American Pediatrics Association, is to “affirm” whatever troubled teenagers think, put them on irreversible puberty blockers and prepare them to have their bodies permanently mutilated. In fact, this standard of care is malpractice in any reasonable world, but these organizations seem to represent the trans medico-pharmaceutical industrial complex rather than either actual science or the well-being of any patient. By consequence, the Ontario College of Psychologists has retracted Jordan Petersons license. Moreover, the legal battle he has engaged in to undo that decision has not been successful. I doubt that any similar battle would succeed in the United States either, since again, most professional accreditation organizations are private organizations who can legally accredit whomever they chose to.

I have mentioned before how we are witnessing vocabulary distortion at unprecendented levels. The discussion about trans surgeries is yet another example. The faction aligned with the trans medico-pharmaceutical complex will contend that psychological treatment of minors who have been led to think that they have been “born in the wrong body” is “conversion therapy,” a hyperbole that likens such psychological treatment to providing electro-shock therapy to homosexuals more than half a century back. However, I would interject at this point that we could just as well adopt another analogy to the past century and refer to these transgender procedures as “genital lobotomy,” which would not be wrong at all, in the sense that definitely, some lobes are being removed. I am sure that a poll out in the streets will both result in a resounding “no” for conversion therapy and for genital lobotomy in the broad public, who would not be aware that both standpoints cannot be reconciled.

Minors can impossibly understand the consequences of transgender procedures and thereby, cannot give informed consent. Leaked internal discussions from WPATH, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, have confirmed that they were well aware of that all along. Moreover, these procedures are not always successes, to put it mildly. I can only agree with Gen Z social media influencer A.J. Sanchez that such procedures constitute malpractice. I will add on that the surgeons who perform them should be convicted. But nothing of the like happens, since “affirming gender identity” by mutilating bodies of “patients with gender dysphoria” … is the “standard of care.”

Vocabulary distortion seems to lead to all sorts of dysphoria, but it becomes truly dangerous when it involves the law. We have discussed before that the separation of powers seems to have dissolved in Europe and in the United Kingdom, where “incitement” can now pretty much mean “any behaviour the government does not like.” However, the situation can get worse from there, as the defendants in those cases still had a right to legal representation. In a democracy, any opinion has a right to be represented, which includes legal representation. However, Bar Associations seem to be very intensely invested into the mires of “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.” For instance, both the New York City and Alberta Bar Associations organize mandatory DEI trainings, which attorneys need to attend to maintain their license. Such DEI trainings will teach imaginary “truths,” such as the “fact” that white attorneys have been born with systemic racism and they have to “do the work” to compensate for what are, in many cases, past government policies enacted by entirely unrelated people, who also happened to have been white. The American Bar Association has a long list of resources dedicated to DEI and in Britain, the BSB is contemplating a rule change, such that their expected behaviour is not to not discriminate, but to “actively boost inclusion.”

Where is this headed? Well, imagine you are a white, or Asian, student and feel disadvantaged by race-based college admissions. Today, you can file lawsuit, such as the one in which the US Supreme Court struck down “affirmative action.” However, when such behavioral DEI policies engulf Bar Associations, no lawyer would be willing to defend the disadvantaged student, lest they be accused of not portraying the expected behaviour to “boost inclusion” and thereby, lose their bar license.

The effect of the politicization of professional licensing organizations is that institutions will be hollowed out in alignment with political beliefs. Hospitals might as well employ AI instead of human doctors, since the latter will not be able to examine their patients critically anyway. Likewise, courtrooms will still look the same as before: they will have the same wooden, stately interior, but the proceedings that will be allowed to take place there, will be narrowed down to the ones that fit pre-approved narratives.

To avoid getting to such a dire situation, let’s ask the following question: do we actually still need professional licensing boards? The year is not 1750 and it has become pretty easy to check if a person truly has graduated from medical or law school. Conversely, doesn’t anyone who has taken the effort to graduate from such involved studies, have the implicit right to exert the corresponding profession? I see the argument about fraud and malpractice coming, but do we need a licensing board to identify cases of malpractice? Courts are perfectly equipped to weed out those rare cases of truly unprofessional behaviour. Let’s curtail these “professional organizations” to what they should be doing: to advocate for their corresponding professions, and let’s strip them of their power to control narrative. In fact, just like ESG or carbon accounting do not belong in the financial markets, DEI does not belong in the workplace, nor in professional licensing organizations. Both should only be concerned with ascertaining that good quality work is being delivered.

We have been doing as such for a while here at the ranch. We don’t care much if our cowboys are “ICA certified professionals.” What we care for, is that they do a good job, regardless if they are black, green or purple. And I don’t need certification for being a horse either, irrespective of what the North American Farm Animal Association may pretend. Neither should any other horse need to be certified.

(To the interested reader: I have recently been posting short comments and preview snippets on X. A warm welcome to every reader who joins the herd there!)