A new pony has arrived here at the ranch. No surprise, I like her. Friesengeist is a black Friesian mare. She’s affectionate and she treats all horses and cowboys with respect. It’s nice to have her around in the stables. She’s another gentle soul in our herd.

Rancher Bob was very happy that he was able to buy her for cheap too. I overheard him boast about that. “Great deal I made with Four J’s!” he said in excitement. “We had way more hay than we needed anyway. I gave Four J’s a trailer of hay and I returned with a horse in her prime.” Cowboy Jake, who had just finished trimming the edges across the fence, was awestruck. “Why did they ever agree to give you the horse for such a laughable price?” he asked. “I don’t see anything wrong with hat new mare. She’s strong and a very smooth ride.”

“It’s quite a story …” said Bob. He took a sip of water before he told us how he had made the deal. “Four J’s had enlisted her just for fun in the town parade. But they didn’t know that that parade was a qualifier for several other events. The horse would have to parade in five other towns and eventually, every day for a week straight in the County Fair. Four J’s pulled her our of the event when they found that out.”

“But that wasn’t the end of it, right? So how did she get here?” Jake grew a little impatient and wanted to know.

“Well ...” replied Bob, “when they pulled her out, a few activists showed up from some non-profit group called Black Friesians Matter. They threatened to sue because the mare was discriminated against for ‘protected characteristics.’ The guys at Four J’s are really afraid of lawsuits, you know. They once hired a native work student from the rez who did nothing but play games on her phone. They couldn’t get rid of her, though, three times in a row. She first sued them for unjustly being fired as a woman. Since she was one of the few female employees, of course her gender was why they gave her the sack. The second time she sued for being native and the third time for having business hours that were not aligned with shamanic religion. Four J’s didn’t want to go there again. It ended up to be easier for them to simply not own the mare anymore. So they passed her off to a ranch that does not participate in parades. Happy to be the one they thought of.”

If this sounds ridiculous, well, it shouldn’t. Laws in many Western countries contain “anti-discrimination” clauses that define discrimination based on “protected characteristics.” Maybe even more frighteningly so, certain private companies have recently been issuing “community guidelines” or “expected behaviour policies” along these lines as well. Before we go there, let’s first pause and reflect on what motivated such laws in the first place.

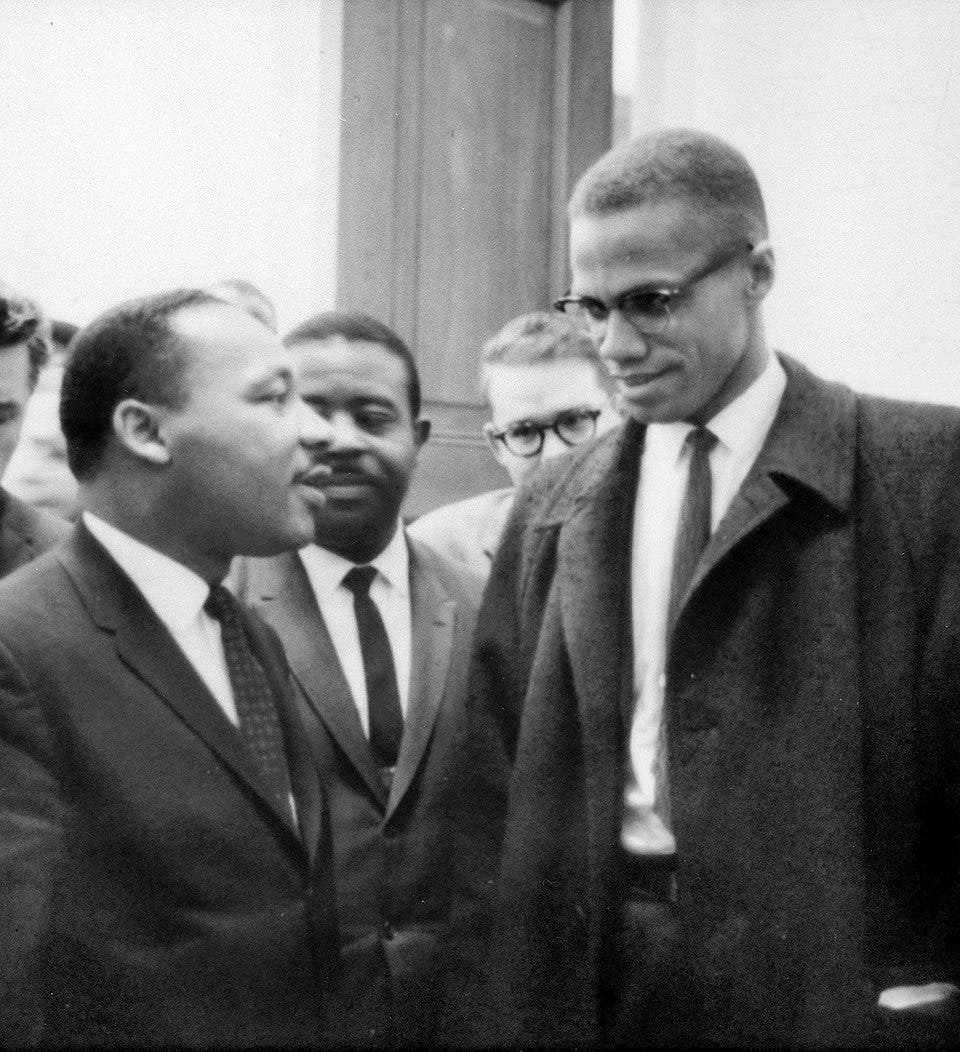

The origin of legal clauses that protect “characteristics” seems to be unambiguously in the United States, where such stipulations started to be used decades earlier than in some other countries. One could argue that to be the case just because the United States also had a much more explicit need to end discrimination than its counterparts in Europe and Oceania. Until the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, spearheaded by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the US was entirely segregated. Black Americans were entirely excluded from participating in many aspects of society. Segregation descended into the most banal aspects of everyday life. For instance, black Americans were assigned separate areas in public transit. Given the baseless discrimination against the black (and native) American communities in every facet of life, it is certainly true that they were excluded from many segments of the job market. Drastic change was definitely called for back in the early sixties.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act was intended to deliver that much needed change and end discrimination against identities. Given the backdrop of racial strife, it is perfectly understandable that the entire body of that text was written with racial discrimination in mind. It should therefore not surprise that Title VII in that act, which focuses on countering workplace discrimination, also intends to end discrimination against certain groups. The wording used, reflects the original (laudable) intent to end exclusion of entire groups from society, by making exclusion “unlawful” for a given set of reasons: “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” Those reasons are commonly referred to as the “protected characteristics.” The original text goes as follows:

(a) Employer practices

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer -

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or applicants for employment in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Title VII stipulates similar protections for practices in employment agencies, labor organizations or job trainings. To its credit, it was written with the foresight that anti-discrimination clauses could lead to undesirable outcomes, such as racial quota. It explicitly prohibits “preferential treatment” in Section 703, clause (j) too.

This approach to counter discrimination was, in many cases much later, copied as a blueprint into other countries’ legal bodies. For instance, the UK’s Equality Act of 2010 prohibits discrimination for “protected characteristics,” just like the Civil Rights Act does. Let it be noted, though, that the British version has added a few “characteristics,” such as “gender reassignment.” One wonders why they did not add “mental delusion” as a protected characteristic too?

The original intent behind the Civil Rights Act was definitely good. It has played a key role in ending crude racial discrimination. The way in which it was worded, though, let the door open for unintended consequences. The text’s direct intent was to make sure that having one or more of the specified protected “characteristics” could not in any way be a liability in an employment context. However, in spite of the clause that prohibits “preferential treatment,” the mere mention of these characteristics has led to them being an asset in some cases rather than a liability.

Imagine being an employee who doesn’t really feel good at work, but doesn’t see alternatives. Such employees typically know that they are not performing all that well. Then, some day, the inevitable happens and their employment is culled. The existence of the clauses cited above may very well lure that person into claiming to have been fired for their one or more “characteristics.” Then they reach out to a law firm that will avidly start a suit against the person’s former employer. In its essence, the lawsuit is frivolous, but as it happens, the employee has the “characteristics” and it may well turn out to be very difficult for the employer to wash the assertion of discrimination under.

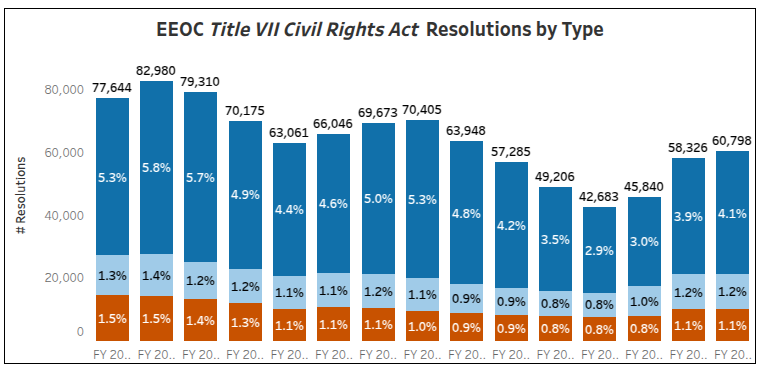

Since this is a very relatable situation, it happens. Let’s have a look at some numbers. Most Title VII claims actually get resolved by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which was notably also created in the Civil Rights Act. It has an interactive data tool that summarizes claims, resolutions and litigations. We can see that, over the last decade, it was common to have over eighty thousand claims filed every year, with roughly 100 to 150 of them leading to litigation.

This does not imply, though, that all of those claims are frivolous. Nor would it be safe to subsume that the lawsuits resulting from them are all frivolous either. In fact, owing to this vast body of lawsuits, there are legal precedents that set the bar as to what can be admissible evidence for a claim of discrimination.

Owing to certain precedents, most of all so McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green (1973), it is generally accepted that plaintiffs must prove their claims of being discriminated against by providing evidence that they:

(a) are a member of a protected class, (b) are qualified for the position at issue, (c) suffered an adverse employment action, and (d) the employer treated similarly situated employees outside of the protected class more favorably (or some other circumstance that suggests a discriminatory motive).

Moreover, Mixon vs. Fair Employment Housing Commission (1987), clause [9], has added that:

While a complainant need not prove that racial animus was the sole motivation behind the challenged action, he must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that there was a "causal connection" between the employee's protected status and the adverse employment decision.

From the above, it may seem that pretty stringent standards are in place to prove that certain actions by employers are discriminatory. However, in practice, the acceptable evidence for a causal connection can consist of “derogatory statements, such as the use of epithets.” That approach can be both reasonable and prone to abuse. Let’s jump into another relatable example.

Imagine a workplace that consists of ten employees. The place is managed by a pretty abusive supervisor, who does not miss an opportunity to point employees’ lack of intelligence out whenever they misunderstand his directions. The supervisor will, almost without exception, call at least one of the employees “a stupid goat” on a regular basis. As a horse, I don’t really see what is wrong with goats and I would not take that as a negative, but maybe that’s just me. However, occasionally, the supervisor will also fire one of his “goats” that he is particularly unhappy with. Now, usually, the employees who are treated like that and fired, are men. As it happens, though, one time, the employee severed is a woman. Well, then in that case, the terminated female employee already has established causal connection, merely by the use of the “gender epithet” of “stupid goat.” It will only take her one or two examples of being treated worse than the others. Any employee who has just been let go can typically come up with a long list of such examples, even if those do not always ring true to former colleagues. In this situation, all employees were treated badly. However, the Civil Rights Act allows only one of them to claim unfair dismissal on gender grounds.

(If you don’t want to terminate Wild Horse Wisdom unfairly, consider to subscribe. We have a free tier. )

The Civil Rights Act was written to make sure that certain characteristics were never going to be a liability on the job market, by protecting them. In practice, though, it has turned said characteristics rather into an advantage than a disadvantage, by specifically providing legal options to those who happen to have one of the characteristics and by blocking that avenue to others. It is time for an overhaul of the wording, in a way that actually makes it more inclusive and more akin to the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King’s teachings.

So far, we have focused on legal action on topics related to employment, membership, or admission in the United States. However, since its inception, the concept of “protected characteristics” was copied in many other places. Most Western countries have adopted it in some way or another, sometimes specifying many more characteristics, like “gender identity.” While the Civil Rights Act already lends itself to preferential treatment for certain groups, it is one thing to define a “protected characteristic” based on a biologically clearly defined concept of expression of sex. It is a whole other thing though, to define such “characteristics” based on properties that can be made up and changed overnight. If an employee decides over the weekend that “they” are no longer a woman called “Suzanne,” but all of a sudden “they” are five persons and need to be referred to as “they/their/those,” then it would be a shame to allow lawsuits to proceed for such employees being fired “unjustly” because their manager only happens to see one person instead of five.

The addition of further “characteristics” to a law like the Civil Rights Act may already seem frightening. Just as damaging, though, is when private companies start to implement clauses inspired by the Civil Rights Act as “community guidelines” or “expected behaviour standards.” These have regrettably become ubiquitous for online platforms and just a part of a collection of “terms and services” that the user has to agree to, to then make use of the “services” of an online platform that only allows the entirely dysfunctional discourse in which nothing can be said “that makes anyone uncomfortable.” We discussed such policies before, with the example of Discord. We have also highlighted that those policies are starting to creep into the physical world, with certain businesses posting standards of expected behaviour for their customers. We mentioned an example from a North American coffee shop before. However, here are the community guidelines from ski and snowboard consortium Ikon Pass. Ikon Pass is owned by Alterra Inc., a corporation that operates many mountain resorts across the globe, with a center of gravity in the United States (and headquartered in Denver, Colo.):

RESPECT AND INCLUSION

• Treat everyone with respect, regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, age, disability, or any other protected characteristic.

• Discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, age, disability or any other protected characteristic will not be tolerated.

• Our mountains are for everyone to enjoy free from discrimination, hate speech, harassment, personal attacks, violence (including threats of violence), and vulgar behavior.

• Respect and protect our natural environment.

I’ll agree that a mountain vacation should be a place to feel free from adversity. But it should also be a place to feel free. A big portion of the excitement about skiing and riding is exactly that it allows to go anywhere on the mountain any time, as one spontaneously decides. That only works in an environment where thought can freely be expressed. Alterra seems to misunderstand that people sometimes have different opinions and that what is considered acceptable in one group, might be considered “hate” in another. Does Alterra know what “hate speech” is? Since governments cannot come up with an objective definition, I trust neither can Alterra. And neither should they bother to. They should just remove these clauses.

The inclusion of “protected characteristics” into laws, statutes and private corporations’ community guidelines, generally leads to a choking environment, in which nobody can express their views spontaneously, which on its turn completely stifles innovation. Society can only move forward when people can think and speak outside the norm.

We therefore need to move forward in a more inclusive way, that includes all opinions, yet still discourages unfair treatment. As to the law, we should ask ourselves why the Civil Rights Act’s authors ever opted to write it as a double negative: it does not allow to not hire based on “characteristics.” Instead, isn’t it much better to rewrite it from a positive premise: to stipulate that one can only hire based on competence and cultural fit, rather than that one cannot not hire for gender? In fact, the law should protect persons, not characteristics. That should be a general principle across societal aspects and not limited to the workplace at all.

As to private companies, well, it is time to reinforce freedom of expression legally. If we fail to do so, we may end up in an environment where quasi-public spaces end up being as suffocating as Britain’s bars will become when banter bouncers are introduced. In the US, however, there are ample legal precedents that have considered places like shopping malls to be public and therefore, subject to the First Amendment. I would argue that skiing mountains and coffee shops also resort under that umbrella. It is time for legislation that enforces First Amendment protections to customers in any establishment that is open to the general public. Regarding online platforms, we should also end the practice of making users sign thousands of paragraphs of legal documents in one click. Users should legally get the choice to opt out of certain clauses.

We horses treat each other equally. We do not give preferential access to hay to horses of any color, or gender. Nor do we give horses extra apples because they think they are more than one horse and want to be referred to by “they/them.” The latter is quite easy to do, though, because… such horses do not exist. People will need to move on from such practices too, but in the meantime, well, let’s enjoy the positive while we haven’t changed the negative. If it weren’t for her characteristics, we wouldn’t have Friesengeist with us here. And we’re very happy to have her. In our herd, black Friesians matter. But other horses matter too.

The British Supreme Court has ruled today that protections for women under the Equality Act of 2010 discussed in my piece only apply to persons of the female biological sex:

https://www.nationalreview.com/news/u-k-supreme-court-rules-males-dont-qualify-as-women-under-anti-discrimination-law-in-landmark-ruling/

They thereby define the term women based on well-established biological science rather than on the imaginary vagaries of "gender identity." A great ruling, but there is still a long way to go. The right way forward is to eliminate the concept of "protected characteristics," as outlined in my piece, and replace it with language that is inclusive to all, not only to those who happen to have "characteristics."