When I saw a red truck drive into our parking lot, I knew who was visiting us. Bruce, the owner of one of the neighboring ranches, walked towards the ranch house and was greeted by Bob out on the porch. Bruce was in tears, something I had never witnessed before. “Hey, what’s up, buddy?” Bob asked. Bruce struggled to be composed, but he eventually said: “I don’t get it… I just wanted to refinance our stirrup manufacture, because I heard rates have gone down. You should be able to get a business loan at three-and-a-half-ish… But what they fucking offered me, is twenty-five percent. Our ranch never had bad credit, but they say my E&G score is too low. I don’t know what to do ... ”

Of course, what Bruce meant, is his ESG score. It is not surprising, though, that he as a rancher did not know what an ESG score was. Neither should he, in a world where we truly believe in equal opportunities. But in times of raging vocabulary distortion, ESG scores are promoted as “bringing fairness into finance.” So what are they, really? We’ll have to get technical for a few paragraphs, but no worries, we’ll return to the gist afterwards.

Environmental, Social and Governance, or ESG scores, have been introduced with the intent to quantify non-financial performance for actors in the financial markets. There is a slight contradiction in this sentence, isn’t there? As the financial markets are efficient, dynamic architectures that allow to maximize profit, it seems odd to create a score to link these markets to non-financial aspects. Financial markets are financial after all.

(If you believe in financial metrics, you could consider to inflate mine and subscribe)

The idea behind ESG is the following: a corporation may have excellent financial metrics, yet may still perform poorly in environmental, social or governance aspects. I would disagree with that line of thought. If a company has to report a significant environmental spill, its share price will plummet. The same will happen when, say, dozens of a company’s employees die in an accident. Markets will react to such events. They will thereby inherently take care that bad actors are punished for their behaviours. The theory behind ESG posits the opposite, though. If true, non-financial aspects of businesses have to be quantified in a separate metric, that then has to be taken into account by lenders and investors.

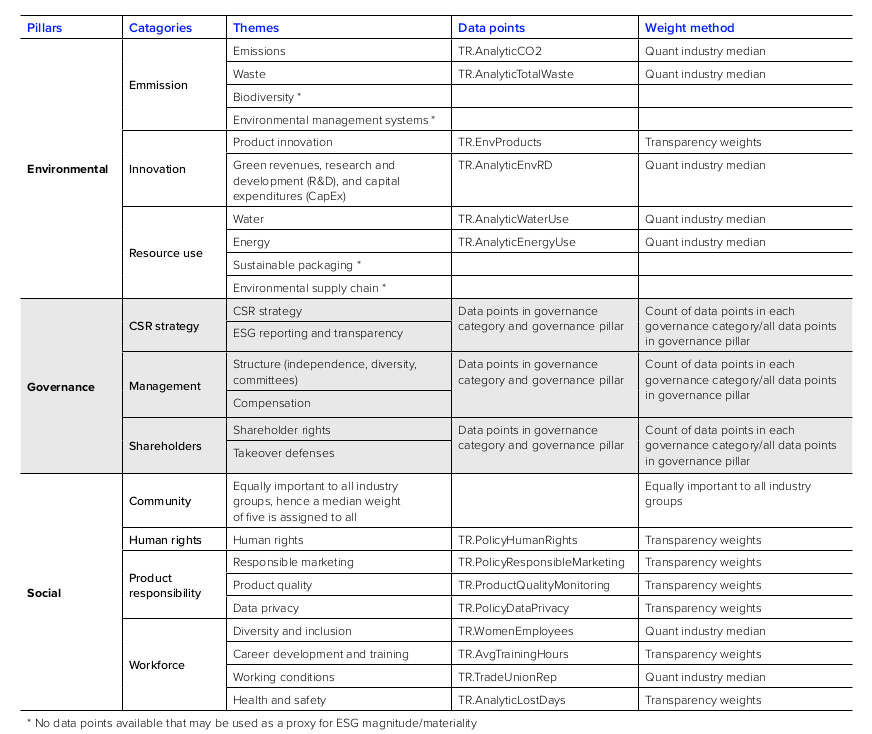

How are ESG scores calculated in practice? Just like for credit scores, there are different vendors, each of which have a slightly different strategy to calculate the corresponding score. However, from a high level, the approaches are similar. Let’s focus on Refinitiv’s ESG score as a representative example. Refinitiv’s ESG scores are calculated as a weighted average of each of the three pillar scores, with environment (44%) being proportionally more important than social (31%) and governance (26%). On their turn, the pillar scores are weighted averages of a set of category scores. For instance, the “E” score will be a weighted average of category scores “Emission,” “Resource use,” and “Innovation.” Again, each of these category scores are aggregates of more detailed “theme scores.” In total, Refinitiv collect data to calculate 186 individual metrics (as counted in a paper from the Bank of International Settlements), which are then further aggregated into the final score in successive stages.

Refinitiv’s ESG scoring looks very thorough, scientific and deterministic, doesn’t it? However, as always, the devil is in the detail. ESG scores are aggregates of aggregates, each of which are eventually derived from numerical input. There does not seem to be as much emphasis on how reliable that input is. Let’s have a a look at each of the pillars.

The E score is composed of three category level scores: “emissions”, “resource use” and “innovation”. Should it surprise us that the ‘emissions’ theme score relates one-on-one to greenhouse gas emissions, reported in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents? Companies are supposed to report these in alignment with the non-GAAP voodoo carbon accounting put forward by the United Nations, which allows to actually reduce the reported number by buying “carbon credits” from other companies, who, for instance, “rewild” citrus groves into pongamia groves. All that matters here is that the activity of the company that sells the “carbon credit” is deemed to “sequester carbon.” Of course, citrus plantations perform photosynthesis just like any other plantation, but citrus groves are categorized as “agriculture,” which does not yield carbon credits, whereas companies that “rewild” can account for the same photosynthesis as a credit.

(If this is the first time you read about “rewilding citrus groves to pongamia groves,” you may want to check out older pony wisdom and subscribe)

Should the E rating still be too high, even after subtraction of “carbon credits,” then the company can still further influence it by performing “innovation.” Innovation will be any number it reports as capital expenditures related to environmental improvements, research and development, or product revenue streams from products deemed “green.” These inputs are highly subjective: they will strongly depend upon each company’s accounting practices. But they are highly arbitrary as well: it matters which activities are deemed “green” and therefore, can be accounted for as “green innovations” or “green revenue streams.”

Beyond the degree of arbitrariness, it should be clear that environmental scoring comes with a huge administrative burthen. The larger the corporation, the easier it will be to comply with the reporting standards and likewise, to influence its E score. The same holds true for the other pillars.

While the E rating may still have some aspects to it that could pose as being based on science, the S and G ratings are worse. The S score is influenced by “societal” factors, such as how much the company spends on “societal initiatives,” or if there is a “diversity and inclusion” initiative within the company, along with metrics on “workforce diversity.” The G score, supposed to reflect corporate governance, gets contributions from themes like “ESG reporting transparency” and “Compensation,” where the latter means: executive compensation. In other words, the G score is partially a self-reinforcing factor: if companies transparently report ESG, G will be higher. Likewise, if the executive team give themselves a bonus for creating a DEI committee, G will be higher.

Should a company still manage to play this game by the rules and, as a result, get a high ESG score, but make statements not liked by the ESG establishment, then there is an additional metric, called the “ESG Controversies” (ESGC) score. The ESGC score is a correction to the ESG score based on “controversies.” Those are based upon counts of “negative press reports” in a broad set of categories. So to make a company with unwelcome opinions toe the ESG line, a negative press report about “rumors” can be launched, which will then immediately lead to a lower ESGC value.

By now, we start to understand why Bruce’s ESG score is low. As a cattle rancher, he is engaged in a very natural and environmentally friendly economic activity. Grass on his land sequesters carbon, his ruminants graze and defecate back, thereby reducing the need for chemical fertilizers and enriching the soil microbiome. Grazing is a by definition a fully renewable and sustainable economic activity. Not so in the books of voodoo carbon accounting, though, where all of his activity is “agriculture,” whence by definition “not green.” While he is not allowed to account for his grass’s carbon sequestration, he does have to report the “methane emissions” from his cattle. Cattle ranching has existed since the ages, so his innovation score is zero. Moreover, as it happens, there are very few classified minorities in the area and Bruce does not have the resources to pay for a DEI committee that adds nothing to the bottom line.

Conversely, MietGiant, a company on the West Coast that manufactures “meat free alternatives” (or in other words: fake meat), has a very high ESG score. Being flush with cash from venture capital backing (not from making profit), MietGiant buys massive amounts of “carbon offsets” and it has the resources to set up ESG and DEI committees and organize a “trans pride” event in its home town. Even its products have novel pronouns. Although these products consume 25 times as much carbon as regular meat, they do count as “green revenue streams” and any investment towards them counts as “green innovation.”

The justification for ESG scoring, according to some, is that it quantifies “ESG risks” and thereby allows for a more precise assessment of an investment’s value at risk. Of course, this is mumbo-jumbo. How much carbon a company emits today, does not impact its future performance at all. Nor is the company at any financial risk for not having a “DEI committee.” On the contrary, I would argue. Such committees are just a feeding trough for a cadre of corporate bureaucrats who fail to have any hard skills and therefore resort to “societally important” topics. They are an effective cost to the company, both by their own wages and resources and by the time they are claiming from other employees in endless, meaningless trainings. Eventually, they also reduce the optimism in the workforce by soft threats to any employee who dare and criticize their practices, such as mandatory compliance to respect any other employees’ preferred pronouns, even if neither the employee’s pronoun preference, nor the actual pronouns existed the day before.

I am not alone to note that ESG reporting has created a huge administrative workload, and thereby cost. Even left-leaning publications have started to spot this. The New Yorker has started to mildly criticize the carbon offsetting industry. Bloomberg is taking heed of the “luxury problem” of DEI and ESG. While a step in the good direction, such publications are not enough.

ESG is a fundamental threat to the structures of our society. It forces companies to engage in costs they otherwise would not. It silences corporate opposition to certain dogmatic beliefs. It can put entire sectors at risk of going out of business and favour others that would fail to make a profit in objective markets. It does all of this by configuring a set of arbitrary targets, which can be changed at any time by the few who have the comfort to be able to select them and any challenge of them leads to immediate retribution. A simple “rumour” is enough to tank an ESGC score, no due diligence needed, no trial needed, but the damage is done. While corporate ESG score already impact individual’s life through their employment, some even want to introduce them at the level of the individual consumer. At that point, the ESG score is the same as one of the most despicable inventions the fascist regime in mainland China ever made: a social credit score.

(If you think mainland China can’t be fascist and communist at the same time, you may want to check out older pony wisdom that examines such directional dysphoria and subscribe)

I am always optimistic. I told you I never complain without providing an alternative. As an investor, I want the companies that I am a shareholder of to be as efficient as possible. I would argue that as they get better at their game, they will produce less waste and consume less energy. Therefore, environmental objectives will inherently be met and do not need to be imposed. I definitely do not want endless reporting burthens mandated onto them, which will reduce profitability and, therefore, my long term return. We can only become unburthened by what has been endless ESG reporting by banning it. So in this case, we need to take a very simple step: introduce legislation that prohibits the use of ESG metrics in any decisions that involve lending. Individual investors can still look at them if they want to, but it cannot be a factor that banks have to take into account when they underwrite loans. Let the market do what it does best: single out what the better investment is. Will it be an index fund or and ESG fund? Let the markets decide.

While this rages on, we can also take measures at the level of the individual business. That is, by making sure that we’re profitable and do not rely on refinancing.

We are profitable at our ranch. We have many visitors and good products and we do have a surplus. We decided to lend the money to Bruce at zero interest. We want our ranch community, its cows and … its horses to thrive!

(To the interested reader: I have recently been posting short comments and preview snippets on X. A warm welcome to every reader who joins the herd there!)